16 fundamental principles for transforming data in a warehouse

The current discourse on data can get a little tiring because of its over focus on tooling. It feels like a new SaaS gets launched every week in the data space. This, however, should not be at the cost of establishing basic, first-principles understanding of data engineering.

Here’s a short list of some fundamental principles for organizing and transforming data in a warehouse. These are concepts that my team and I learned the hard way in the course of building our data warehouse at Omio over last three years.

The list does not address the question of what storage type to use (data lake vs warehouse vs marts), nor obsesses over Kimball vs Inmon vs Linstedt style of modeling. Instead, it addresses concerns that are somewhat orthogonal to these choices.

As you will notice, this is a highly opinionated set of guidelines. The reader is advised to not treat these dogmatically, nor get triggered by some seemingly extreme views. Most of these principles are very contextual, of course. YMMV. :-)

Principles for Data Transformations (in no specific order)

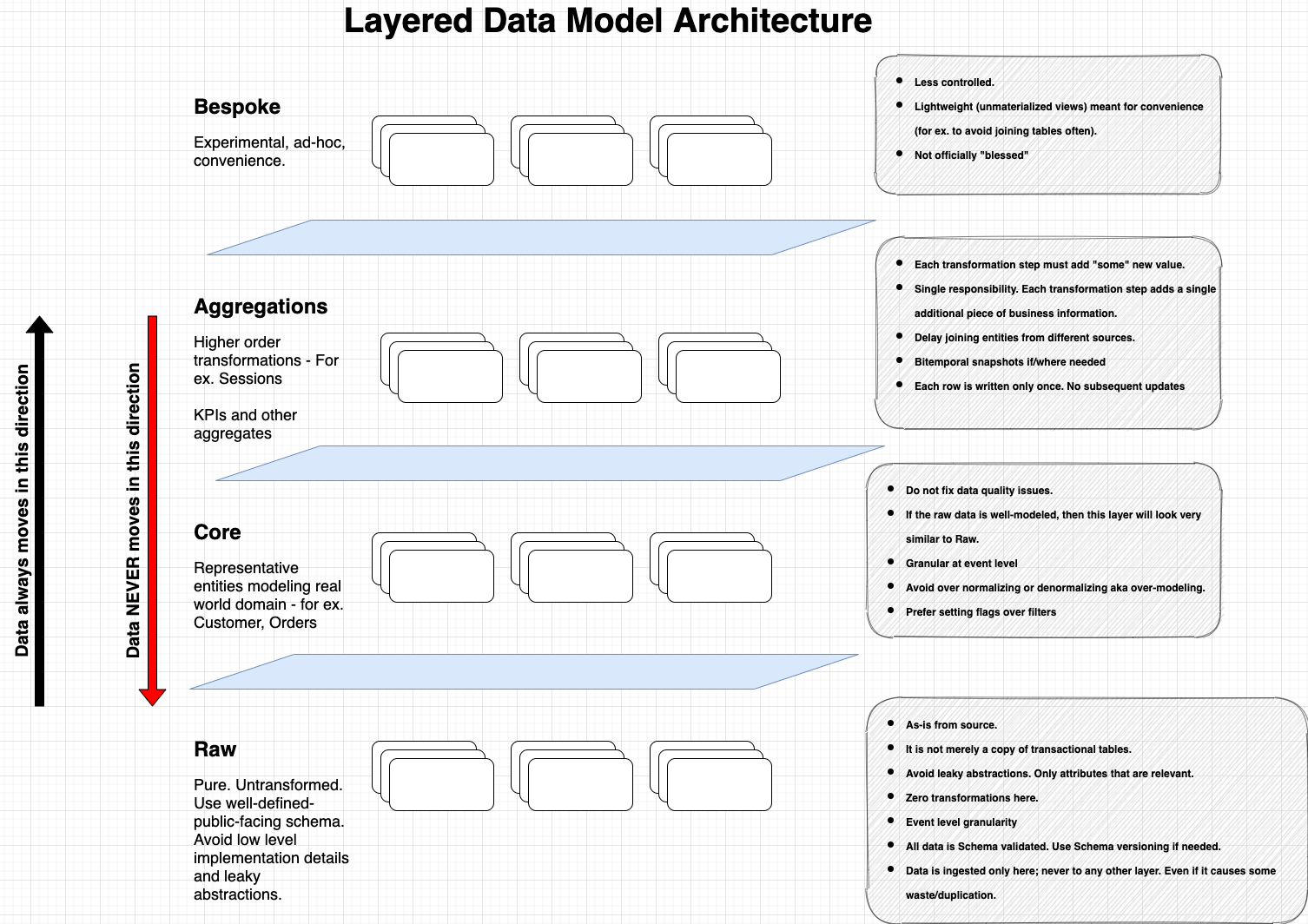

- Organize your storage in layers such as shown in the above diagram.

- Avoid querying source tables that are more than 2 layers below the target layer.

- Practice immutability. Each row should written only once to the table. In other words, do not insert a row and then update it in a subsequent step.[1]

- Break complex transformations into smaller sub-steps. Adopt single responsibility.

- Delay joining tables from different data sources. Decoupling helps manage changes better.

- Ensure that all Facts/Events have a business timestamp and an arrival/etl timestamp.[2]

- Perform upserts by primary keys only. Never delete-insert based on timestamps alone.

- Avoid upserts if you care about bitemporal history.[3]

- Avoid cleaning data. Cleaning data is an anti-pattern. If you must, do this in a separate step in the transformation flow.[4]

- Do not model anything motivated purely by ease-of-use or convenience. Each transformation step must add “value”.

- Never re-implement any business logic from source systems in the warehouse.[5]

- Use un-materialized views wherever possible for aggregations (Views are relatively cheaper to build and modify, but have some limitations)

- Do not create/invent any fundamentally new domain entities directly in the data warehouse. If you must, do this deliberately and not as a side-effect of another transformation.[6]

- Do not coalesce multiple attributes into a single attribute. Coalesces are hard to reason about. Instead, use records/structs to store multiple values.

- Do not model anything in a visualization layer like Tableau/Looker. These models are hard to reason about and can not be reused outside the tools.

- Create multiple usage-centric views/aggregations of the same data instead of creating a Frankenstein’s dataset.

- (yeah, I know I said 16 😄). Adopt an evolution strategy for your tables using principles of API evolution. Create a new version, communicate to users, migrate and deprecate.

Footnotes

- Jorge asked a great question about immutability vs GDPR requirements for removal of data.

- Having an etl timestamp (i.e. the time at which the data was inserted in the table) is useful to identify the incremental subset of data that arrived since the last time a batch ETL was run. Even for streaming jobs, the concept of processing time is often useful.

- Often useful for financial reporting where you want to maintain the history of all changes to a record.

- Data cleansing should be an “exception”, not a norm.

- This can happen due to leaky abstractions from source data.

- Say your core domain has a “user” entity but not a “customer” entity. A customer is a user who bought something. In this case, avoid creating a “customer” entity in the data warehouse. This is because the definition of the entity can be arbitrary and subject to changes based on how the domain evolves. If you must, then do this in the

aggregationslayer.